THE LEGENDS OF SPRINGHEEL JACK

THE LEAPING TERROR OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, AND A FEW LATER APPEARANCES!

JOHN RIMMER

In January 1838 the Lord Mayor of London received a remarkable letter at his official residence at the Mansion House. It was from somebody signing themselves 'A Resident of Peckham' and reported on strange happenings in what were, at the time, the small villages that lay around the south and west of London.

'Resident' claimed that a group of men from "the higher ranks of life" had taken a wager that they would visit these villages, sneak into gardens and attempt to terrify the inhabitants by appearing in frightening disguises such as ghosts, a bear and the devil. These monsters had already "deprived seven ladies of their senses", two of whom "are not expected to recover. But likely to become a burden on their families".

The Lord Mayor was rather taken aback by this letter, but decided that Peckham lay outside his jurisdiction and concluded that as the culprit had not entered the City he "could not take cognisance of its iniquities"

But Peckham was not the first of London's outlying villages to be visited by this frightening apparition. Now a fashionable suburb, in the early nineteenth century Barnes was an isolated village beyond the south-western edges of London, alongside a deserted and marshy 'waste', Barnes Common. In January 1838 the Morning Chronicle reported that "four months since" (i.e. September 1836) a figure in the form of a huge white bull had attacked a number of women on the Common.

Shortly afterwards the attacker appeared again, in the nearby village of East Sheen, this time in the form of a bear. The apparition then moved on to the riverside townships at Richmond and Ham. As the scare spread, the ghostly figure was reported across all the small towns and villages that spread out from the south-western edges of London, including Hampton, Hampton Court, Twickenham, Hounslow, and Isleworth.

It was at this point that the strange shape-shifting creature began to take on the supernatural human form which gave it its eventual name. According to the Morning Chronicle report the creature was an "unearthly warrior" in a suit of armour, with clawed gauntlets and springs on its shoes. In Isleworth an unfortunate carpenter was attacked by the armoured monster in the appropriately-named Cutthroat Lane (probably actually a corruption of ‘Cut-through Lane’). He put up a vigorous fight but the newspaper report claims that two other ‘ghosts’ came to the assailant's aid, and tore the unfortunate victim's clothes to shreds.

At this stage the apparition was still being described as a ‘ghost’ but the word was not intended supernaturally, as the general assumption was that the attacks were the work of a group of aristocrats intent on scaring the 'lower orders' out of their wits.

In February 1838, responding to the scare a group of concerned citizens formed a committee to investigate the affair. They were told that the attacks were being organised by "rascals being connected with high families", and that the wager was one of £5.000 that they could "destroy the lives" of thirty people, "eight old bachelors, ten old maids, six ladies' maids and as many servant girls as they can", and frighten them to death.

As this story was circulating, Springheel Jack launched the attack which was to define his appearance and methods for most of the rest of the nineteenth century.

Before the development of the London docks and the expansion of the East End, Old Ford was a small village on the banks of the River Lee. On the outskirts of the village, in Bearbinder Lane (now part of Tredegar Road), 18-year-old Jane Alsop answered a knock on the door of the cottage where she lived with her parents and her two sisters. It was nine o'clock in the evening, and very dark in this isolated area.

When Jane opened the door she was confronted by a man wearing a dark cloak who claimed he was a policeman and asked Jane to bring a light, as "we have caught Spring-heel Jack right here in the Lane." Jane went back into the house and came back carrying a lighted candle which she gave to the figure.

At that moment the 'policeman' flung open his cloak, and in the words of the report in The Times for 22 February 1838, "applying the lighted candle to his breast, presented a most hideous and frightful appearance, and vomited forth a quantity of blue and white flames from his mouth, and his eyes resembled red balls of fire."

The figure attacked the girl, scratching at her clothes with claw-like fingers. As Jane attempted to flee back into the house the creature followed her, nearly ripping her clothes off and tearing at her hair, but Jane was eventually pulled away from its grasp by her younger sister.

Even after they had locked the door against it 'Jack' continued banging and shouting, until the household called for help from an upstairs window.

The next day Jane and her family travelled to Whitechapel to report the attack to officers of the newly-formed Metropolitan Police, who sent two officers to investigate.

They soon came up with other reports of a tall, cloaked figure wandering around the lanes of the area and frightening passers-by. Indeed, some of the people who rushed to the Alsop's house after hearing the family's cries said that they had passed a tall cloaked figure who told them that the police were needed at the Alsop's. At the time they took no particular notice of him, but on reflection concluded that he was in fact the culprit.

A couple of local characters, a bricklayer named Payne and a carpenter named Millbank were questioned about the attack, Millbank protesting that he was too drunk to remember what he was doing at the time. Susan Alsop however maintained that her attacker was not drunk. In the end despite further police investigations and other witnesses coming forward, no-one was charged with the attack, and no further information ever came too light.

On the 25th February, while the hue and cry was still going on in Old Ford, another knock on the door alarmed a young servant-boy at a house in Turner Street, off Commercial Road in the East End, when he opened the door to a man who asked for the householder, Mr Ashworth. Before the boy could answer the figure threw off his cloak and, in the words of the Morning Herald "presented a most hideous appearance".

The young lad screamed in terror, which was enough to send the figure rushing off before taking any further action. There did not seem to be any police follow-up to this incident, although the fact that ‘Jack' knew the householder's name would suggest that he might have been a local person aping the Old Ford incident.

In fact there were a number of copycat incidents at the time, which resulted in prosecutions. A man attacked the landlady of a West-End pub with a club, shouting that he was Springheel Jack, but fortunately he missed his target. In Lincoln's Inn Fields a woman was attacked by an assailant who grabbed her and captured her inside the cloak he was wearing, saying “it's no use struggling, I am Springheel Jack". The woman fought him off, but not before he struck her in the mouth.

Jack's third East London manifestation came on 28th February. This more resembled the original attack on Jane Alsop than the Commercial Road incident or the copycat assaults, in that there is another report of mysterious fiery breath

A young lady named Lucy Scales, along with her sister, were making their way home along Green Dragon Lane, a long-vanished passageway off Limehouse's Narrow Street, near the river. They saw a figure ahead of them lurking in an angle of the alley. As the couple approached the cloaked figure, it turned to Lucy and spurted a blue flame into her face. This temporarily blinded her and she dropped to the floor. According to a contemporary newspaper report she fell into violent fits for several hours.

Lucy's sister, who was behind her when the attack took place described the assailant as tall and thin, wearing some sort of head-dress which at first she took to be a woman's bonnet. When the figure attacked her sister, as with the Old Ford Jack, he held a light, a 'bulls-eye' lantern, up to his face before blowing a flame into Lucy's face.

Lucy and her father reported this to the Magistrate Mr Hardwick at the Lambeth Street Police Station at Mile End. This was same magistrate who had examined in the evidence in Jane Alsop's earlier attack, and he concluded that both attacks were perpetrated by the same person.

Although copy-cat attacks continued in the London area, and further afield, most of these were easily attributed to local offenders. Two typical reports came from Kentish Town in north London.

A youth was arrested after jumping out of hiding at women passing by, shouting "Here's Springheel Jack". To add to the effect he wore a mask, which had blue glazed paper emerging from the mouthpiece to try to give the effect of flames. After a night in the cell he was discharged with a caution, and the mask was burned.

A police constable investigating another Springheel Jack in the district laid in wait, and was confronted by a figure running and leaping out of an alleyway towards a group of children who ran off in fear. Apprehending the culprit he discovered him to be a local man "who was considered of weak mind", wearing a bright blue mask. The magistrate who preside over the case seemed to be remarkably forbearing. The Examiner newspaper account records:

Mr Rawlinson to Prisoner, "What have you to say?

Prisoner (with vacant smile) "Why it was only a bit of fun, that's all; I meant no harm"

Mr Rawlinson: "Well I'm inclined to think so, you're discharged, but don't do it again."

Springheel Jack seemed to take a break from tormenting Londoners, but Mike Dash, a historian of strange phenomena, has tracked his later appearances around the country. Jack first moved up to Yorkshire, where the Leeds Times of 19th May 1838 reports his appearance in the seaside town of Whitby. The elaborate journalistic language of the period sometimes makes it difficult to gauge whether the report is to be taken seriously or not:

"Within these last few days this mischievous personage has visited this borough, and disturbed the quiet of many of its peaceable inhabitants in his nocturnal wanderings"

However, his actions seems serious enough. The paper reports that he attacked a woman tearing her clothes from her and attacking her with his claws, leaving her face "much injured and disfigured". As in the earliest London reports, this figure is described as being disguised as a bear. The woman could give no clear description of her attacker as "her terror was so great that she could give but a faint description of his person".

The report again seems to assume a light hearted mode, saying that "Mr Spring-Heels mysteriously disappeared" but there is no description of giant leaps or other preternatural abilities. It is an interesting coincidence that sixty years later Whitby was chosen by Bram Stoker as the place where Count Dracula first set foot in Britain. Was Stoker aware of the Springheel Jack connection when he chose this town to introduce his own phantom terror?

There was still a strong belief that Springheel Jack was the result of the activities of some decadent aristocrat and his cronies, members of a revived 'Hellfire Club'. The prime suspect was the notorious Marquis of Waterford, who was certainly the ringleader of a group which was responsible for vicious attacks on random individuals. He is said to be responsible for the phrase 'painting the town red' as that is quite literally what he and his cronies did at Melton Mowbray after a drunken day at the races.

His character certainly fitted into that of the rogue aristocrat taking on outrageous wagers that occasionally resulted in serious injuries. However Waterford married and seemed to settle down to a quiet country life in Ireland, dying in 1859 as the result of a horse riding accident. But Jack's activities continued well after that date.

Nearly twenty years after his first appearance in London Jack was haunting the Black Country, to the west of Birmingham. There are reports from 1855 of him visiting Old Hill, midway between Dudley and Halesowen.

Reports claim that he was seen jumping across the road from the roof of the Cross Inn to a butcher's shop opposite. Witnesses described him as a "frightening figure" with horns and cloven hooves. Police are alleged to have found hoof-prints on the rooftops. A local superstition soon arose that to see Springheel Jack meant sudden death.

Thirty years after his original rampages, Jack re-appeared back in his old leaping-ground of Peckham, South London. Peckham was by then no longer a small village lying outside London, but had been swallowed up into the capital's rapidly expanding suburbs.

On 19th October, 1872, the Camberwell and Peckham Times denounced a "rascally night bird" scaring women in the Honor Oak neighbourhood, and calling for action against the prowler. The challenge was taken up by a "party of Peckham Gentlemen" armed with a "comfortable" cudgel, but their vigilante patrols did not seem to produce any result.

The first clear account of Jack's reappearance is reported in the same paper for 26th October, and tells of a servant-girl working at a house in Lordship Lane. After returning from collecting beer for the family supper she was asked to go out on another errand, but complained that a man was lurking in the road near the house.

Her employer, a Mr Smith, reassured her that he would watch from the window, but the moment she went out into the front garden a white figure leapt up from behind a hedge. She screamed and ran back, but at that moment Mr Smith ran out to help her, tripped over the step and fell right onto the girl. Thinking that the apparition had claimed her in her clutches the girls screamed, "went into a fit, in which she remained two hours, and is now seriously ill."

The description of the figure given by Mr Smith is that it was about six foot tall, wearing a dark overcoat which was flung open to reveal a white lining to give a ghostly effect. The figure wore a dark hat with feathers, that concealed its face.

Other local residents confronted a similar spectre, including the daughters of the Head Master of Dulwich College and their governess. A figure dressed in white with its face masked appeared in front of them as they made their way to the College chapel, but it made its escape before they could raise the alarm. Again, the paper reports that the young ladies' health suffered as a result of this confrontation.

By now Peckham seemed to have been in a state of panic, with the local paper giving instructions on how to make a cosh studded with nails. It pointed out that such a 'life preserver' could be "remarkable elegant". Vigilante gangs patrolled the streets, and some youths went out at night dressed in women's clothes, presumably to act as bait for the villain, until the police advised that they went home and changed or "it would be the worse for them".

By November the local paper was running a regular 'Ghosts of the Week' column, recording the latest incidents. Through the whole course of the panic, the apparitions were never referred to locally as anything other than 'ghosts' and usually in the most derogatory terms: "The scrubby mortal designated The Ghost", or "the arrogant pretender".

But soon accounts emerged of Springheel Jack's preternatural nature, although at first they were taken less than seriously, and the paper carefully noted their origins in local public houses, and amongst the builders and navvies working on the rapidly expanding housing developments.

In the first such case on the 2nd November, George, an itinerant musician who played in local taverns turned up at the Edinburgh Castle pub in Nunhead Lane, in a state of great distress and covered in mud. The Camberwell and Peckham Times was keen to note that he told his tale "having somewhat recovered himself by two or three pulls of potent liquor".

He had been walking through a brickfield when confronted by a figure "about seven feet high, all white with its face in a blaze". Here at last was something closer to the description given by Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales over thirty years earlier. George ran off in fright but the 'ghost' followed him, the chase only ending when he climbed through a hedge and fell into a ditch - hence his mud covered state.

The following night the 'Ghost' then appeared at the Linden Tavern, by Nunhead Cemetery, where it tapped at the window, provoking the customers, mostly navvies working on construction sites, to give chase. They pursued it alongside the cemetery wall, but it evaded them by jumping over a six-foot fence into the site where a reservoir was being built.

The next day near the same spot, yet another serving-girl collapsed in panic when a tall figure in white suddenly sprung up in front of her.

The area was now full of rumours of the ghost. The sight of a young girl who had fallen off a ladder and was being carried off on a stretcher to hospital started rumours that the creature had been killed. A group of youths dressed one of their number in white clothes and carried him through the streets to jeering crowds, and rumours again circulated that the trickster was an aristocrat involved in a cruel wager to frighten to death the very young and the very old.

The local paper's popular 'Ghosts of the Week' column was filled with stories of encounters with the Ghost, or explanations as to how he created his frightening appearance. Others told of various misunderstandings which led to claims that the ghost had been seen, one involving a scuffle between two men who each imagined the other was trying to steal a pig, its squeals gathering a crowd who thought they were seeing an attack by the ghost. In one street a ghost was burnt in effigy, with fireworks and a street party.

A letter to the paper reported an encounter at Herne Hill, with a figure that leapt over some railings and ran off across the fields at great speed. The write claimed that he wore a black suit and wore spring-heeled or rubber-soled boots "for no man living could leap so lightly and ... fly across the ground in the manner he did last night".

Eventually a vagrant called Joseph Munday was arrested and charged with loitering and frightening a young girl by jumping up in front of her in her garden, waving open a black cloak with a white lining and causing her distress. He was bound over on a surety of £10 to be of good behaviour for the next six months.

Some people doubted that he could have been the cause of all the incidents, because as one person commented, he was "a clodhopper who could not run the length of a street without being captured". Even after his arrest there were some further incidents, but eventually the panic died down, and Springheel Jack left Peckham for a second time.

In 1877 the reports of Jack's exploits reappeared. He seemed to have moved westward from London, to the Army camps at Aldershot, which were regarded as 'the Home of the British Army'. On the 17 March a report appeared in the camp's military newspaper, Sheldrake's Aldershot and Sandhurst Military Gazette, which reported some 'questionable larks'.

The story was that an unidentified individual had approached a sentry at the camp and refused to identify himself when challenged. He was described as "dodging about the sentry box in a fantastic fashion" and made off "with astonishing swiftness". The sentry fired at him, but apparently missed his target.

The idea of 'Springheel Jack' was by now so well-established in public perception that a writer for the Gazette - 'Cove', who seemed to have a weekly gossip column - immediately described this prankster as Jack: "Springheel Jack has not been heard of, I believe, since the little affair with the sentries"

The story was picked up by The World newspaper and later reprinted in the Illustrated Police News, a paper which made even today's sensationalist tabloids look tame when reporting crime stories.

The Police News immediately latched onto the Springheel Jack angle, suggesting that the figure could jump ten or twenty yards at a time and that there were two pranksters who performed their tricks aided by powerful springs in the heels of their boots. The fact that the sentry’s bullets did not stop him, rather than demonstrating the sentry's poor aim, was evidence that he was impervious to bullets.

Rumours circulated around the camps that members of one or another regiment were perpetrating the pranks at the expense of other regiments, particularly as there was a pause in his activities when sentries at the camp were issued with live instead of blank ammunition, but started again when the use of blanks was resumed. But after a few alleged incidents later in the year, Jack's visit to Aldershot appears to have been brief and unspectacular.

But he wasn't finished, and after South London and Berkshire, his next appearance was to the east. This time the Illustrated Police News is our only source.

The cover of the 3rd November 1872 edition carries a startling engraving of a figure clad in some sort of animal skin with a long tail, leaping onto the Newport Arch, a fragment of the Lincoln's old Roman wall. A gun-wielding figure leans out of a window in the roof of the adjoining building firing a pistol at him, and a crowd of people on the street below throw stick and stones at the apparition.

But according to the Illustrated Police News, who claimed that Jack had been disporting himself in the area for several days, the bullets and guns had little effect and Jack was able to leap 15 to 20 feet onto rooftops and make his getaway.

The authenticity of this story is doubtful, as diligent search by researchers has failed to find any reports in the local Lincolnshire papers for the period.

By the mid-nineteenth century Springheel Jack had become what we would now call a 'meme' - "an idea, behaviour, or style that spreads from person to person within a culture", a free-flowing concept which could be used culturally in a variety of contexts.

Jack began to find himself represented in popular fiction, the so-called 'Penny Dreadfuls' forerunners of today's comic books. These were luridly illustrated weekly publications, filled with heroic accounts of Imperial adventures and sensational crime stories.

In some stories Jack was portrayed as a vengeful crime fighter rescuing damsels in distress, but other stories showed him in his traditional form as a fire-breathing monster, or a decadent aristocrat. He is always depicted in dramatic costume, with a helmet and cape, in many ways the precursor of modem superheroes such as Batman.

He also appeared as a character in popular and very bloodthirsty theatrical productions along with figures like Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber. Sometimes the two characters seemed to merge into a generic urban folk-demon.

His next major appearance was in North West England at the end of 1887 and the first months of 1888. The Cheshire Observer of the 29th October 1887 reported that "he is in the Wirral, and making a tour of the peninsula". Like the original London attacker, the story circulated that he was trying to satisfy "a wager of £1000 that he could visit every village in the Wirral in character as Jack.”

Although it was not claimed that his aim was specifically to terrorise a certain number of people, that seems to have been how it transpired. The Observer reported: "The alarm which has been created among children and weak-minded persons in the district is quite unprecedented, and many persons who have seen, or fancied they have seen, the ghost are suffering from the effects of the shock, one person at least to the writer's knowledge being confined to her bed."

All the usual characteristics that had come to be associated with Jack were present on the Wirral phantom: "his favourite form of dress is that of a tall gaunt female or a military officer with a long cloak". He supposedly covered his face with a phosphorescent substance to look like a ball of fire, and that he wore an outfit made of rubber smeared with grease so that it was impossible to catch hold of him.

Again, the local newspapers of the period seemed determined to mix fantasy and wild rumour into their reports. Surely no-one was expected to believe that "he vaults over high houses with the greatest of ease, and on Thursday last week he broke the high leaping record by springing to the clock of the [Birkenhead] Town Hall and altering the fingers".

The story spread to the Manchester papers, which reproduced the Cheshire Observer's stories, adding that police in Wrexham had arrested a young man who had been posing as Springheel Jack in a local cemetery, hiding lighted candles in the shrubbery to enhance the ghostly effect. He was fined 16 shillings, or could serve 14 days imprisonment. It is not recorded what option he took.

Jack was also springing around across the Mersey in Liverpool, but for an account of his actions we have to rely on the memories of an elderly gentleman who recalled an incident from 1888 to Richard Whittington-Egan, author of a number of books on Liverpool history, people and curiosities, in the nineteen-fifties.

He told Whittington-Egan that he recalled an incident when he was attending a boys’ club at St Francis Xavier's school in Haig Street, Everton, when there was a commotion in the street outside. A boy rushed in to say that Springheel Jack had been seen in nearby Shaw Street and William Henry Street. When the boys rushed out they found a crowd of people in the street searching for the figure, which they said was hiding in the shadow of a church steeple. The unnamed boy did not see anything himself.

This may have been a confused memory, and there is no contemporary report in the local press. We will see that William Henry Street was later the site of what has generally been considered Jack's last appearance, and it is possible the man may have been confusing memories of this. However, there is some evidence that gives greater credence to this story.

Folklorist and local historian Peter Rogerson has discovered that in January 1888 Jack put in another appearance in South Lancashire, in Wigan. A report in the Lichfield Mercury – local papers would often reproduce curious stories from other parts of the country – begins by referring to "the notorious Spring-heel Jack who created so great a sensation some few months ago in Liverpool, has been alarming the inhabitants of Wigan".

Two coalminers in the Standish Lower Grounds area were pursued by a shrouded figure, and later a young lady was scared by the apparition to the effect that, as seemed to be typical of such encounters, "she has been unwell since".

Here the identification of "Springheel Jack" seems to be the newspaper's convenient label rather than a description of the apparition's appearance or actions, as at no point does the report give any description of superhuman leaps or fiery breath. It concludes with the suggestion that Wigan's Springheel Jack is "none other than an ardent lover who has been prohibited from visiting his loved one (the young lady who was rendered 'unwell'?) and that he has determined to avenge the ungracious treatment" .

Most accounts of Springheel Jack conclude with his second appearance in Liverpool, in 1904. The definitive popular version of the legend is given in Whittington-Egan in his book Liverpool Colonnade, first published in 1955.

He begins his story: "It is just over half a century since Spring-Heeled Jack, the Leaping Terror, set the good people of Everton trembling in their houses ... echoes of that old fear linger in the memories of elderly folk ... who have lived most of their lives in that part of Liverpool, and remember being told by their mothers, 'Spring-Heeled Jack will get you if you don't behave yourself'."

Whittington-Egan goes on to give a history of Jack's appearances, retelling many of the exploits described above in highly colourful terms and in some cases with wildly inaccurate details, beginning with his version of the Liverpool events:

"It was on a late September's day in the years 1904 that the legendary figure of fear dropped in on the startled Evertonians, and hundreds of people watched in fascinated horror while the fantastic creature hopped up and down the length of William Henry Street. The extraordinary spectacle continued for some ten or twelve minutes".

He described Jack as making "gigantic bounds", some of over 25 feet, and across the streets from rooftop to rooftop, until finally after leaping across the houses to Salisbury Street he is never seen again. In Liverpool, at least.

Unfortunately for this account researchers have been unable to find any report of Springheel Jack's exploits in the Liverpool newspapers of the period. The only available contemporary printed account from the comes from the notoriously sensationalist News of the World, published in London.

However there was something else going on in Everton at the time. A day before the News of the World story was published, the London Star reported on a house in the district being attacked by what we would now call a poltergeist: "Pieces of brick, old bottles, and other missile came hurtling down the chimneys of the haunted house ... the annoyance was so persistent and the terror among the neighbours so great that the residents of the house left hurriedly and the place was closed".

It seems possible that over the years this episode became conflated with the earlier Springheel Jack stories from 1888 in the same area of the city. However, during the 1960s the TV personality Fyfe Robertson presented a report for the early-evening BBC TV show 'Tonight' in which he interviewed witnesses to an early twentieth-century century Springheel Jack case, presumably the 1904 Liverpool incident.

But although most classic accounts of Springheel Jack end at this point, there have been many incidents since, both in Britain and around the world, which have kept his name alive.

The industrial town of Warrington lies just twenty miles east of Liverpool, and the memory of the incidents in that city may have led to local people identifying a mysterious intruder into their own community as Springheel Jack.

In August 1927 a local paper, The Warrington Examiner, boldly headlined a story "A Ghost in Galoshes: Hue and Cry in Haydock Street".

"In the early hours of Sunday morning the whole neighbourhood was thrown into excitement by the news that a 'ghost' had been seen. It was stated that between the hours of one and two o'clock a 'tall figure dressed all in white' was seen passing along the streets adjoining Haydock Street and completely disappearing from time to time."

As by now seemed to be the pattern for Jack's appearances, "two women who witnessed the apparition were so overcome that they fainted and had to be revived by the crowd which soon assembled."

By Sunday night the whole area was in uproar, and hundreds of people had arrived from across the town, armed with spades, carving knives, bottles, brooms, and as seems traditional for such mobs, pitchforks!

The crowd gradually grew sceptical of the story, until at 11 o’clock a figure suddenly appeared and the mob set off in pursuit. The apparition ducked down a narrow passageway until confronted by a high wall which it leapt over with agility. One witness described it as being like "the famous Springheel Jack", but there was no suggestion that the figure wore spring-loaded boots, as another witness claimed that the 'pit-pat' noise it made suggested the figure was wearing galoshes.

The incident seems to have spread panic around the neighbourhood with many women and children fearing to go out alone into the streets, and for over a week groups of young vigilantes patrolled the area armed with stick and canes, but their searches did not uncover the culprit.

Stories of a mysterious ghost and frightening faces appearing the windows of houses recurred a few weeks later, and a crowd armed with pokers and household implements chased a figure which eluded them again by jumping over railings onto a railway embankment. The crowd in hot pursuit pulled down the railing to follow it, but it escaped by vaulting a ten-foot high corrugated iron fence – at least according to a rather sensationalised report in the Warrington Examiner.

The more conservative Warrington Guardian dismissed the stories as "silly pranks", and quoted the local police superintendents as dismissing the whole scare as "more than anything else, that it is hysterical women who have 'got the wind up' and imagined most of the things which are reported." And with that it seemed Springheel Jack left Warrington.

It is clear, reading these historical accounts that there was not one 'Springheel Jack', and that there are as many variants of the creature as there are people who have seen him, claim to have seen him, thought they had seen him, or even wanted to have seen him.

The fire-breathing monster, the dissolute aristocrat, the prankster, the deranged hoaxer, the pantomime villain and the ghost have all had their part to play in the growth of the legend of Springheel Jack. But by the middle of the twentieth century he began to take on a new identity—an alien.

Throughout the nineteen-forties and fifties much of the world became entranced by reports of mysterious flying objects, and the stories of people who claimed to have met the occupants of these alleged craft.

'Appointment with Fear' was a popular British radio series which ran from 1941 to 1953. It's presenter, billed as 'The Man in Black', was the character actor Valentine Dyall, whose rich, deep voice was ideal for dramatising stories of mystery and horror. He was later the voice of 'Deep Thought, the computer in the TV version of 'Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy.'

In 1954 he wrote an article for Everybody's, a popular picture magazine, in which he suggested that Springheel Jack could be a creature from another planet. He wrote:

"Today we are still without a likely answer to the question: who—or what—was the fabulous, ubiquitous creature that terrorised a huge section of the British public for nearly sixty years? One thing is certain—he was no ordinary mortal. It is significant that a high proportion of those who saw him were convinced that he was not of this world, but either a spirit or a visitor from some distant planet."

The article was accompanied by a very imaginative artist's rendition of two sentries at Aldershot, confronted by a bizarre glowing figure floating above the ground, wearing a helmet looking like some kind of strange sea creature. The caption describes it as "wearing a gleaming helmet of fantastic design, breathing blue flame". There was, of course, no mention of helmet or flame in the original Aldershot reports.

In a subsequent issue of the magazine, a correspondent suggested that Jack was indeed a visitor from another planet, and this explained his prodigious leaps. Jack's home planet was much larger than earth, the writer speculated, and with much stronger gravity. A visitor from such a planet would have no difficulty leaping great heights in earth's weaker gravitational pull, he claimed. The creature might also have a much longer lifespan than earthlings, allowing it to continue its spectacular activities for a hundred years or more.

This line was taken to its logical conclusion in an article published in the magazine Flying Saucer Review in May, 1961. Although having a small circulation, this magazine was influential amongst researchers into strange phenomena. The writer, J. Vyner, claimed that Springheel Jack was indeed an alien. He presented a dramatised and often inaccurate account of Jack's early 1838 appearances, claiming that the flashes of light and flames that his victims reported were caused by the actions of a 'ray-gun', his giant leaps aided by "the possession of a device for neutralising gravity".

Vyner's thesis seemed to be that Jack was a spaceman who had been accidentally deposited into 1830's London, and his movement around the southern villages and suburbs was in search of a 'safe house' where he could await his rescuers.

Vyner's account not only exaggerated and distorted the original reports, but he also introduced details of his own. According to Vyner, Jack wore a "tall metallic helmet", and he had ears that were "cropped or pointed like that of an animal", descriptions which appear in none of the original accounts.

The Flying Saucer Review article fitted neatly into a theme that was growing amongst 'ufologists', as people who investigate UFO reports call themselves, that many strange historical phenomena could be explained as visitations from extraterrestrial creatures, that were misunderstood by earlier generations.

One such was the so-called 'Mad Gasser of Mattoon'. This was a spectral figure which in 1944 invaded houses in the small Illinois town of Mattoon. People began reporting being confronted by a figure which sprayed some kind of noxious substance into their homes. Although over two dozen people claimed to have been attacked and anaesthetised by the gasser, no conclusive evidence was found of its activities. Explanations ranged from mass hysteria or the work of a mentally disturbed individual, to a supernatural entity or a visitor from space.

Other scares featuring Springheel Jack-type entities have been reported from communities world-wide. Between 1938 and 1944 the New England resort of Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod was haunted by 'the Black Flash', a creature, 8 feet tall, with eyes "like balls of flame" which could vault over high walls after leaping out at terrified citizens.

During the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in World War II there were rumours of a figure known as the 'Spring Man' which leapt out to terrify pedestrians in the narrow alleyways of the Old Town. Many Czechs regarded him as a symbol of defiance to the curfews imposed by the occupying forces.

The history of Springheel Jack is confused by constant repetition of what is described as 'fakelore'. Stories are transferred from writer to writer, without checking sources and with details being added to make them more dramatic or to make the story fit the storyteller's own views and theories. Alternately, details which tend to de-mystify the story are left out. The fact that many of the nineteenth-century Jacks were local people who were caught and prosecuted is often left out of later accounts.

There are also the problems of memory, when perfectly sincere individuals confuse major details of an incident. This may be what happened with the reports of Jack in Liverpool in 1904. Many years later, elderly 'eyewitnesses' telling their stories to Richard Whittington-Egan and Fyfe Robertson may be unconsciously mixing up elements of the 1888 story which perhaps they heard of from their parents, with the 'poltergeist' incidents of bricks being thrown down chimney-pots - both seemingly involving sinister characters surreptitiously moving about the rooftops of the local streets.

But some other stories were just completely made up. The first full length book on Springheel Jack was by Peter Haining, a prolific writer and compiler of books on a wide range of supernatural phenomena.

His book, The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring-heeled Jack radically dramatises the accounts of his anti-hero's activities, and in some cases he seems to have made them up entirely. He is keen to identify the Marquis of Waterford as responsible for the early London incidents, at least. In his account of Jack's visit to the young servant boy in Turner Street he introduces the detail, completely absent in any contemporary record, that the comer of the assailant's cloak bore the elaborately embroidered letter 'W'.

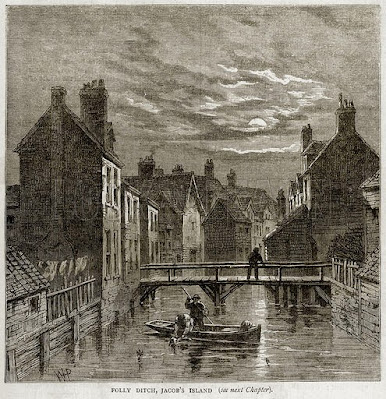

This is not the only piece of elaborate embroidery in Haining's accounts, however. He gives a long and dramatic description of the attack and murder of a prostitute, Maria Davis, in the notorious Jacob's Island slum, for which there is also no contemporary record. He even reproduces a contemporary engraving showing men in a boat on one of the foul waterways that threaded through the Island, claiming it depicts the recovery of Maria's body, but researcher Mike Dash subsequently traced the original and discovered it had no connection to the alleged case.

Newspaper reporters in the nineteenth century were also notorious for adding speculative detail and personal comment to their reports, and were free and easy in their descriptions. Although many of the early reports described Jack as a 'ghost' this did not seem to imply any supernatural qualities, but simply that he was an elusive figure who could not be apprehended.

The persistent reports of servant girls and old maids falling into a fit for days on end clearly implied that the reporters thought this was a sensation only likely to affect the uneducated or the infirm. And when impostors posing as Springheel Jack began to appear before the magistrates, the newspapers would be careful to point out their mental and physical frailties, their unprepossessing appearance and their tendency to drunkenness.

For most of the nineteenth century Jack became a rumour, a hobgoblin, a figure that mothers would use to threaten misbehaving children. As the memories of his original antics faded, the character built up by the media – newspapers such as the Illustrated Police News, penny-dreadfuls, sensational theatrical shows – took over from accounts of any actual expedience.

So was it all just rumour and speculation from the popular press? The clearest and most detailed accounts we have, shorn of later elaboration, come from the newspaper descriptions of the original East London incidents, and reporting on the details of the magistrate's inquiries, and the correspondence from the concerned residents of the villages south of London in 1837 and 1838.

The idea that a group of ‘young bloods' might be touring those still isolated communities and amusing themselves by scaring the wits out of what they no doubt saw as 'the lower orders' is by no means improbable – we can imagine a supernaturally-inclined Bullingdon Club – and it is certainly quite possible that the Marquis of Waterford may have been involved in at least some of these events.

We can be certain that somebody – or some thing – did actually attack Jane Alsop at Old Ford, and Lucy Scales in Limehouse. The verbatim accounts of the magistrate's examination make this clear. The attack on the boy in Turner street is less well documented, but seems to fit the pattern of the other two incidents and there seems no reason to doubt it. These could all be the activities of some malign individual with their own weird motives.

The first use of the phrase 'Springheel Jack' seems to have been by the figure who attacked Jane Alsop: "For God's sake bring me a light for we have caught Spring-heeled Jack here in the lane!" This might imply that even that early on in the story the phrase was in common use, and Jane would be expected to understand what her visitor meant. But once this phrase entered the language it provided a hook for any kind of mysterious, threatening or just mischievous incident.

Who was he? A decadent aristocrat, targeting his lust at young, vulnerable girls in the lonely suburbs; a deranged creature of the night, his clawed fingers slashing at prostitutes in the fog-filled alleyways of the city, or a phantom, unconstrained by fences, walls, defying not just the law of the police, but the law of gravity?

Was he something created by the very fact that he had been given a name, a name that instantly touched something within ourselves? A name that meant that the fears and frights that lurk in the dark places of our cities and our minds could be contained in the figure of one leaping monster.

Springheel Jack belongs to a category of urban ghosts that seem to hover uncertainly on the boundaries of reality, rumour, the supernatural and fiction. As a Victorian archetype he shares characteristics with both Count Dracula and Jack the Ripper. Many later accounts of Jack's exploits seem to elide both Jacks, Ripper and Springheel, and the Vampire. The image of a billowing back cloak down a dark alleyway, the face glowing with phosphorous or wild blood-filled eyes, the blade slicing through the darkness and the final disappearance into the shadows of the feeble gas-lamps, becomes the shadow itself.