PETER ROGERSON UNEARTHS THE STORY OF THE LAST WITCH IN WARRINGTON IN THE LOCAL PAPER

by Peter Rogerson

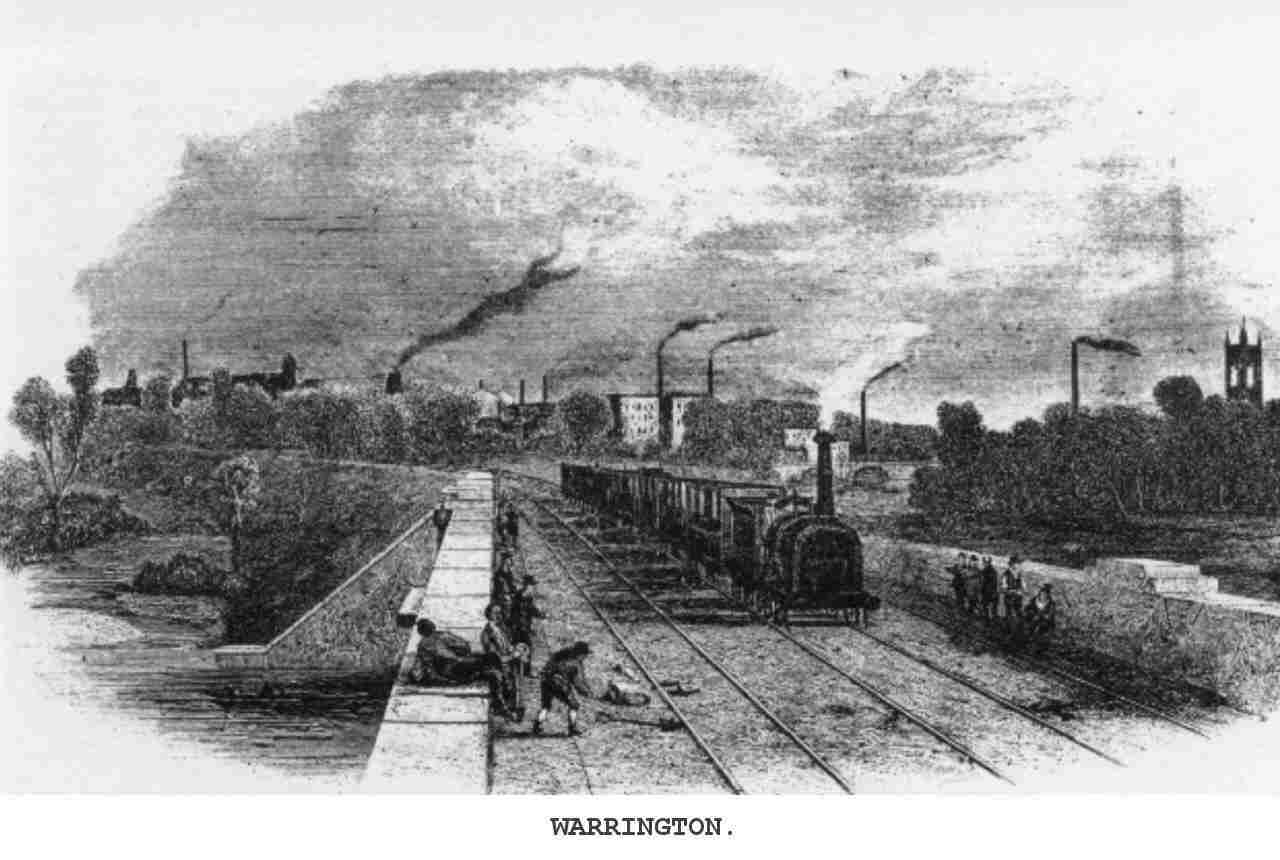

We associate the late survival of witchcraft beliefs into the Victorian age with remote rural settlements, so it comes as surprise to see them associated with a quintessential Northern industrial town.

Warrington, between Manchester and Liverpool, was in the mid Victorian period rapidly growing industrial town, drawing in people from all parts, including not just the surrounding areas of Lancashire and Cheshire, but from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Midlands and Black Country. Unlike the traditional Lancashire mill towns it was far from a one industry town, with traditional industries such as tanning, textiles and tool and pin-making, vying with the new big industries of brewing, soap and chemicals and heavy iron and steel. Between 1871 and 1881 the population rose from 29,984 to 40,957.

It is against this background that the following story appeared in one of the main local newspapers the Warrington Examiner 16 September 1876.

Alleged Witchcraft

A man and his wife named Jackson were summoned for beating an old woman named Maria Platt, aged 84 years of age. She stated that during a dispute about the right of placing a clothesline in the yard at Dial Court, the female defendant struck her with a clothesline and her husband knocked complainant down and threatened to kill her. When on the floor she received blows from both of them. In answer to the defendants’ solicitor she denied that she got a living from telling fortunes, but said that the defendant, Mrs Jackson, had cups, cards and glasses for the use of fortune tellers which she offered to sell her. The defendants’ solicitor said his witnesses would not come up to court, as the complainant bore the reputation of being a witch and a fortune teller and neighbours were afraid that if they gave evidence against her she would bewitch them. Parents would not let their children come and were afraid to come themselves. It was very lamentable that there could be such gross and ignorant superstition in Warrington but such was the case. The bench considered the case proved and fined each of the defendants (£1) and cost and bound over to keep the peace for 6 months.

It is always difficult to accurately assess the value of money, but £1 in 1876 would probably buy goods equivalent to £60-£70 in today's money, but in terms of average earnings it was more like £500.

The main rival newspaper also reported the case, their report contained a number of errors, but did give voices to the people involved. Maria Platt says

“(A)t dinner time...Mrs Jackson went up to her door and used very abusive language towards her and afterwards attacked her, and beat her with a clothes line about the head. (Mr Jackson) then came up and struck her on the face and knocked her down. She was then picked up by some of the neighbours, and was being taken down the yard when (Jackson) cam up and knocked her down again, her face striking the ground and maintaining a severe cut. She had never given the least provocation and though it was shame that her at her age she should be subject to such treatment.”

The only witnesses are for the prosecution Ellen Reaney or Ready who said “she saw Mrs Jackson with the clothes line several times. When witness interfered (Mrs J) struck her also. (Mr. J.) came up and knocked the old woman down and abused her in many ways. Another witness Alice Thompson, Maria’s next door neighbour also reported seeing the two women fighting and that she saw Mrs J knock the old woman down and strike her with a clothes line.The defence solicitor, Mr Bretherton, said “there was some dispute between the two parties about putting up a clothes line, and the old woman interfered with Mrs J to hinder her in putting it up. This led to a dispute, but he denied that any brutal assault was committed. The old woman was accused of being a witch by her neighbours, who were afraid that she would bewitch them and they dare not go past her door in consequence. It was a very sad thing that such ignorance should exist in a town like Warrington, and that a poor old woman like her should be thought to have such power, but such was the superstition.”

What can we make of this story. Well, for a start, witchcraft accusations have often been assumed to be the product of the tensions of small face to face societies, and you couldn’t get more face to face than in a place like Dial Court. (Wider area along with a modern map can be seen here)

Dial Court, a narrow cul-de-sac off Dial Street was in a dense urban essentially slum area, People were literally in each others face, Things like hanging out washing really needed to be organised on a rota basis, and neighbourhood disputes would have been common.The two families involved in this case are also of interest, they were not members of the industrial proletariat, but rather on the precarious lowest rung of the petty bourgeoisie. Census and birth marriage and death indexes show something of their background.

Maria Platt was born Maria Morris in Holywell, Flintshire in 1793/4. At the rather late age of about 30 she married Henry Platt, a baker in the little village of Grappenhall just south of Warrington on 22 September 1824, but Henry died in 1846, leaving her a widow. By 1871 she was living with her son Henry, described as a baker, but not owning his own business. The Warrington Guardian index 1853-66 showed Henry in the courts several times, as both a defendant and plaintiff. After Maria died in 1879 he went further downhill, and by 1881 he was a pauper in the workhouse.

As the Platt’s are on the fall, the Jackson’s are on the rise. In 1871 John Jackson was a coachman, but by 1881 they had a grocer’s shop in Dial Street itself which they will hold for at least the next twenty years. We can perhaps make a guess at the root cause of this conflict. Maria Platt has been telling fortunes as a way of making money and keeping out of the workhouse. Then John and Ann Jackson arrive on the scene and Ann goes in for fortune telling herself, only she can afford fancy equipment and tarot cards. At some point Ann offers to sell some of this fancy equipment to Maria, knowing she can never afford the price. A bitter neighbourhood quarrel develops and Maria gets the reputation of being a quarrelsome person, with a son rather prone to fights, which adds to her reputation as a witch.

If Maria is the stereotypical village witch, then Ann with her occult equipment is much closer to modern new age beliefs. These two women then represent the link between the village witch and the modern new practitioner.

(Copies of the original newspapers can be consulted in the local studies search-room at Warrington Library.)